React Hooks — Migrating from Class to Functional Components — A Tutorial

JavaScript is a funny language. At least, I think it is, but mainly because of my software engineering learning path.

Let me get this out of the way before we dive into React Hooks. I’ve used a myriad of programming languages since I began coding: C, C++, Java, JavaScript, Python, MATLAB, Octave, Visual BASIC, and even Assembly. A programming language is just a tool. Use the right tool for the right job. If a person claims to be a carpenter, but only knows how to use a hammer, he/she might as well be Thor.

Cool huh?

Cool huh?

You haven’t met this kind of problem yet.

You haven’t met this kind of problem yet.

Okay, enough comic humor.

The point is, as a software engineer, you always need to keep learning, and right now, React JS is a valuable tool to have in your toolkit.

React Hooks — Why They are Cool

JavaScript loves functions! You can work in Object-Oriented Programming with JS, but most JS programmers hate classes. In fact, under the hood, every JS class is actually a function posing as a class (true story).

One annoyance that React developers faced was the inability to attach state (memory) to functional components. This is what React Hooks have come to change.

With Hooks, you can replicate almost every use-case for state in a functional component, and completely ditch class components.

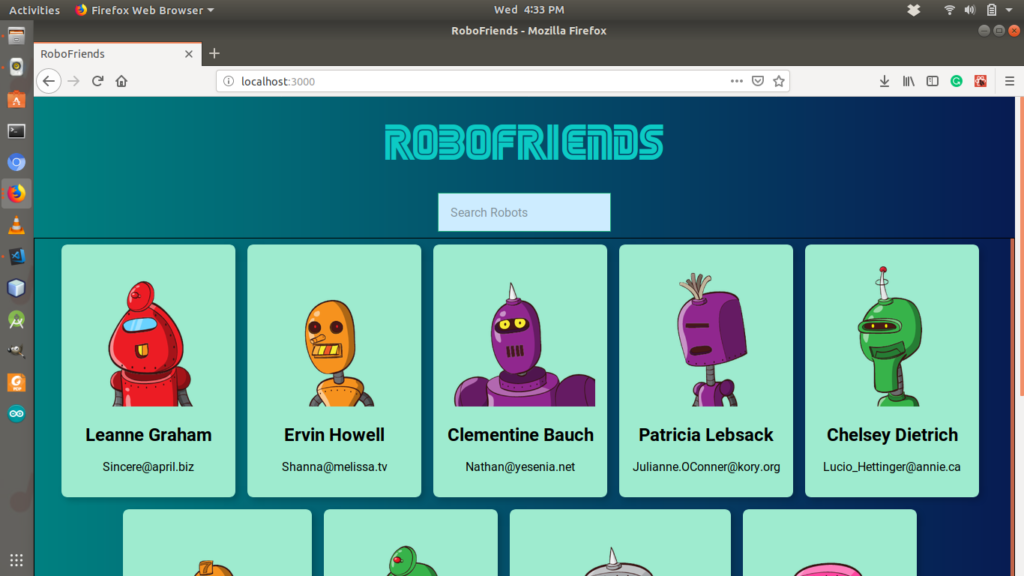

To clearly illustrate, I’m going to show you a small demo of how I converted an existing class component to a functional component in a working React project. The project, RoboFriends, was created originally by Udemy instructor, Andrei Neagoie.

Although it’s a simple project, you should at least be comfortable with basic React and JavaScript terminologies. I will not be able to explain every term in this short post. Knowledge of Git will also be helpful.

Let’s dive in.

RoboFriends

The source code can be found in this GitHub repo. Be mindful that the link points to the react-hooks-start branch. The finished work is on the react-hooks-end branch. I intend to leave these branches unmodified for future reference.

Clone the repository to your local machine and run the command: npm install in the directory.

We want to switch to the appropriate branch now: git checkout react-hooks-start.

Next, run npm run start. If all is good, and you have a good internet connection, go to localhost:3000 in your browser, and you should see a screen like the one shown below:

If you would like to build this from scratch, I would encourage you to try either of these courses by Andrei on Udemy, based on your current skill level. They are: The Complete Web Developer: Zero to Mastery and The Complete Junior to Senior Web Developer Roadmap. RoboFriends is just a small part of both courses, but the rest of the course material is pretty darn good if I say so myself.

Okay, so you’re all set up, but at the time of writing we need to take one more key step before we move any further!

According to the React docs, React Hooks is in alpha at the time of writing this article. As such, you might not be able to use them in the normal releases of react. You actually have to update the NPM packages to the alpha version. Run this:

npm install --save react@16.8.0-alpha.1 react-dom@16.8.0-alpha.1

This will update the version of React and React-DOM used in your package.json. In the future, you won’t have to do this manually.

EDIT: Hooks comes bundled with Create-React-App these days. You won’t have to manually set your React Version to use them anymore.

You can check to make sure you did not break anything.

Now, all our code is in the src folder. This project was created with create-react-app, so the directory structure is pretty standard. You will find two sub-directories in the src folder: components and containers. Our class components are in the containers folder: App.js and ErrorBoundary.js. Our functional/stateless/dumb components are in the components folder. This is simply by convention.

We will focus on our containers. Remember we want to convert our class components to functional components with state.

This is what our App.js looks like right now:

The first thing we want to do is to convert the class to a function:

class App extends Component{

//our code

...

}

should become…

function App(){

//our code

...

}

… or if you like…

const App = () => {

//our code

...

}

If you have ES Lint enabled, it will probably begin to complain about your constructor. That’s simply because functions don’t have constructors. All we do in our constructor code is to initialize state, so let’s quickly use Hooks to replace the constructor:

//Swap out named component import for useState from 'react'

import React, { useState } from 'react';

function App(){

//replace constructor function with these lines

const [robots, setRobots] = useState([]);

const [searchField, setSearchField] = useState('');

//extra code

...

}

useState is a hook that is used to assign and manipulate local state (think memory) for a functional component. Two things are commonly done in a constructor: initializing state and binding ‘this’. Functional components do not need a ‘this’, making binding unnecessary. useState, can therefore easily replace this.state, as well as this.setState, eliminating the need for a constructor. It basically works like this:

const [statefulVar, statefulVarSetter] = useState(initialArgForStatefulVar)

If the above syntax looks funny, we are using a JavaScript concept called array destructuring. It’s a neat shortcut.

ES Lint is now complaining about our componentDidMount method. React Hooks provides us with a hook that easily replaces three life cycle methods: componentDidMount, componentDidUpdate, and componentWillUnmount.

Say hello to useEffect. We can use useEffect in place of componentDidMount in our code like this:

//remember to import useEffect

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

function App(){

//replace constructor function with these lines

const [robots, setRobots] = useState([]);

const [searchField, setSearchField] = useState('');

useEffect(() => {

fetch('https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users')

.then(res => res.json())

.then(users => {

//this.setState({ robots: users })

//becomes:

setRobots(users);

});

});

//extra code

...

}

Basically, our componentDidMount fetched data from an API, converted it to JSON (a JSON array), and assigned that array to the robots state using this.setState. We do the same thing, but use setRobots this time.

useEffect simply takes a function to run in place of componentDidMount and componentDidUpdate. If you have any function to clean up after a component (something that should usually go in componentWillUnmount), simply return that function at the end of useEffect. We do not need to do so in this small example.

Next, our onSearchChange handler method can become a regular function. It is already an arrow function, so let us put a const in front of it. Now, we will change the this.setState call inside it to use the setter method our state hook returned. Here’s what I mean:

const onSearchChange = (event) => {

setSearchField(event.target.value);

}

The last major block is our render function. We do not need a render function in a functional component, so cut out all the code from the render block and delete the function call as well as its opening and closing braces.

Paste back the code you cut, and we can now delete the line that says: const { robots, searchField } = this.state;

We can delete it because robots and searchField are already stateful variables that we can access directly due to our useState calls at the start of the App function.

The next block, which is the declaration and definition of filteredRobots does not change at all, since we are already referring to the robots variable directly. You can take some time to convince yourself that this is true.

Finally, our return statement spits out some JSX depending on the number of robots in our robots array. We use the ternary operator, but the logic translates to:

if robots.length is zero (i.e. false), we print “Loading…” to the screen. If it is not, we render some components: a SearchBox and a CardList wrapped in ErrorBoundary and Scroll components.

We have only one thing to change here. Change the prop passed into the SearchBox componentfrom this.onSearchChange to onSearchChange, with reference to the handler function. Remember, our functional components do not have to deal with ‘this’.

What was our return block now looks like this:

const filteredRobots = robots.filter(robot => {

return robot.name.toLowerCase().includes(searchField.toLowerCase())

});

return !robots.length ?

<h1 className="tc">Loading...</h1> :

(

<div className='tc'>

<h1 className='f1'>RoboFriends</h1>

<SearchBox searchChange={onSearchChange} />

<Scroll>

<ErrorBoundary>

<CardList robots={filteredRobots} />

</ErrorBoundary>

</Scroll>

</div>

);

If you’re wondering about our weird classNames ('tc' and 'f1') in the JSX, we’re using a CSS library called tachyons. It’s a really neat library.

Our full code now looks like this:

Save the file and check to make sure nothing is broken.

Congratulations!!! Our code is now functional, and I dare say more readable and easy to understand.

There is one more class-based component: ErrorBoundary.js, but we will leave this as a class-based component.

The reason is simple: at the time of writing this tutorial, the componentDidCatch life-cycle method has no equivalent hook, and we need to use it in our ErrorBoundary component.

The above point is evidence that Hooks are still in their early days. At the time of writing this tutorial, React Hooks are still in Alpha. According to the core React team, they have no intention of taking classes out of React, so rest assured, your old class-based projects are safe.

I hope you enjoy React Hooks as much as I do. Happy coding!

KayO